A Vasculitis Long-Timer Relies on the Power of Connection

When Sharon was diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis in 1981 at age 30, there was no Internet for her to turn to. In the lab where she was working, she found a medical book with a single paragraph of information about her disease: “If not treated,” it said, “vasculitis is fatal within five years.” She closed the book and decided there was no other choice: she was going to learn to live with it for as long as she could.

When Sharon was diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis in 1981 at age 30, there was no Internet for her to turn to. In the lab where she was working, she found a medical book with a single paragraph of information about her disease: “If not treated,” it said, “vasculitis is fatal within five years.” She closed the book and decided there was no other choice: she was going to learn to live with it for as long as she could.

Luckily, Sharon did get treatment. A year after she started experiencing unexplainable symptoms, like a strange sense that her arm was not getting enough circulation, she was put on prednisone. While the high-dose corticosteroids came with a side of “chipmunk cheeks,” she felt revitalized. “Prednisone gave me a lot more energy,” she said. “No matter the task, the guys at work used to tease, ‘Sharon will have it done in 30 seconds.’” Despite what she read in the lab book and her real sense of uncertainty, her optimism grew. This wasn’t the death sentence the textbook predicted.

In fact, as Sharon slowly tapered off prednisone and stretched the time between her rheumatologist visits, a new sense of purpose arose in her. “Vasculitis changed my life,” she said, “because it put me in the direction of helping people…When you’ve got a rare disease, it’s hard to find answers.” Sharon wanted to be a resource and a source of support for others on this journey.

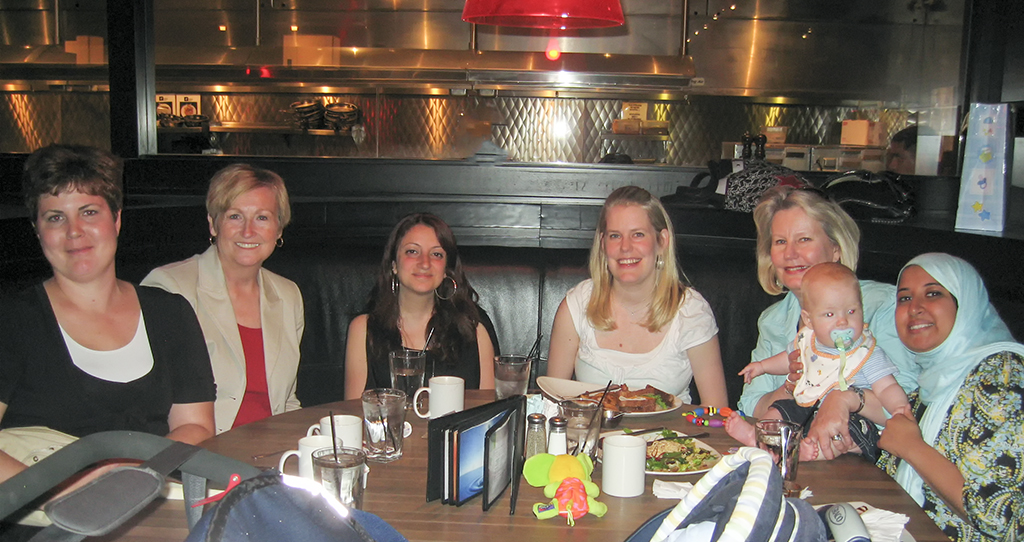

In 2005, armed with nearly twenty-five years of lived vasculitis experience, Sharon decided to start a support group for people living with Takayasu arteritis near her home in Ontario, Canada. At the first meeting in March 2005, four women showed up for lunch in Toronto. Today, three of those four original members are still part of the group.

Over time, the group grew into a rotating mix of 10-12 people meeting for lunch a few times a year. Sharon felt purposeful in her role as support group leader. Many people came to the group after having been newly diagnosed; her nearly three decades of experience with the disease equipped her with a rare perspective and knowledge, which she was eager to share.

For Sharon, support groups are game changers, especially when you’re living with a disease few other people have even heard of. “At our lunches,” Sharon said, “you’re with your peers and they understand what you’re going through. You can compare medications and share what’s working for you.” Sometimes, this spurs one group member to go back to their doctor and ask about a new medication or a new way of dealing with their disease. “For example,” Sharon explained, “when we talk about tapering off prednisone, some people want to rush off of it. Those of us with experience remind them, ‘No, you don’t want to rush it.’” There’s something really nourishing, Sharon said, about being able to “just sit, relax, and talk and not have to explain yourself.”

Sharon hasn’t stopped there. She also volunteers as the Vasculitis Foundation’s (VF) area contact for people with Takayasu’s in Canada. In other words, if a newly diagnosed individual reaches out to the VF seeking to talk with someone in their shoes, Sharon’s willing and ready to connect with them. “I know how hard it is to deal with something no else gets,” she said, “Or how hard it is to be told, ‘Well, you don’t look sick.’ I just want to give back what I’ve learned.”

But it’s not just about giving back: Sharon believes that innovation is possible when we join forces. When people living with the disease connect and share their experiences with each other and with doctors, researchers, and the world, they pool their knowledge and build a foundation for discovery. “If we get together,” Sharon said, “it’s possible we can find a cure in our lifetime.”

It has been almost forty years since Sharon first read that her disease could be fatal within five years. A lot has changed since then. Beyond the advent of the Internet and online support groups and reliable information being available through organizations like the VF, “the technology,” Sharon explained, “has greatly improved.” Sharon, who needed a balloon angioplasty to get her vasculitis diagnosis in 1981, says that, today, the disease is “a lot less invasive to diagnose.” Not only that, but new therapeutics have emerged—and more are on the horizon. There is hope.

As a veteran, Sharon continues to have a lot to offer those who are newly diagnosed. She was on a VF support call recently when someone new joined. When this new person heard that Sharon has been living with Takayasu’s for forty years, her “eyes bulged.” She had been feeling anxious and uncertain: What will happen now that she has this new disease? What’s possible for her future? Sharon’s presence was a reminder: life is still possible. You can still look to the horizon. Sharon’s advice to her? “Don’t try to do it by yourself.”

Sharon’s Toronto support group stopped meeting in person when the Covid-19 pandemic shut down the world in 2020. Next month, they’ll be returning to their first in-person lunch in four years. “Everyone’s quite happy,” she said. Perhaps that’s the key to longevity: discovering that even on the rarest of paths, you’re not alone.