Annie Reynolds laughingly tells her mom she is her glitch child. She says she has been a monster – making her siblings walk on egg shells – she has been depressed and she has been scared. Annie was diagnosed with GPA vasculitis at 14.

Annie, now a 21-year-old graduate student, has written an illustrated children’s book about her vasculitis journey. She shares all of her emotions and even her chipmunk cheeks, the result of a prescribed 150 milligrams of prednisone a day, in her book. The steroids were designed to keep her going until she got a diagnosis for her rare disease. During those years she recalls being angry – and hungry – all the time.

Annie, now a 21-year-old graduate student, has written an illustrated children’s book about her vasculitis journey. She shares all of her emotions and even her chipmunk cheeks, the result of a prescribed 150 milligrams of prednisone a day, in her book. The steroids were designed to keep her going until she got a diagnosis for her rare disease. During those years she recalls being angry – and hungry – all the time.

“After years of learning to manage my symptoms, I’ve gained strength and resilience, and I am now passionate about sharing my journey with others—especially children and teens facing similar battles,” Annie says. “I’m deeply committed to being an advocate for young people with vasculitis, offering support to both them and their families.”

She says her diagnosis “was a big scary thing for me, my parents and my siblings.” Because she sees more children and teenagers being diagnosed, she hopes by sharing her story she can “show positivity. There is another side to it. I want to be a voice of hope and strength for those in the vasculitis community.”

Something Wasn’t Right

Annie was an 8th grader when she first started having symptoms. She played soccer but often complained to her coach about joint pain and she began losing weight. That summer she left for camp and when she returned her mom could see something was seriously wrong. After being told she was anemic and that it wasn’t unusual for her age, her family decided to go on a planned family trip to Florida. On that trip, Annie and her mom spent most of their time in the emergency room. She and her mom went to Rocky Mount Children’s Hospital Colorado as soon as they returned home. She was quickly transferred by an ambulance to Children’s Hospital Colorado where she was an inpatient.

“I needed a blood transfusion. I was meeting all kinds of doctors. It was a mystery and they couldn’t figure out what it was,” she says. ““A month later, I was starting high school all alone – a month after everyone. I was a scared freshman who was embarrassed by the way I looked and felt.”

She started complaining about having bad breath. That’s when the doctors noticed her nasal cavity was deteriorating, which ultimately led to her GPA diagnosis. She was prescribed steroids and then Rituximab.

“Since then, I’ve been navigating life with this autoimmune disease and its many challenges,” said Annie, who is now a graduate student at Texas Christian University (TCU), where she is studying early childhood education, language and literacy. “I always connected with nurses when I was first going through this. I want to be an advocate for kids and help them go through the things I have had to go through.”

Encouragement

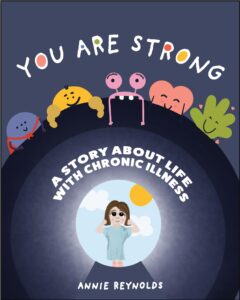

That desire, and a graduate class assignment, prompted her to write a non-fiction picture book. She titled it “You Are Strong, A story about a Life with Chronic Illnesses.”

The book features Annie’s journey through diagnosis and treatment as a child and the emotions and side effects she experienced.

Annie, who made the field hockey team during her sophomore year at high school, was in remission by her junior year. Even though she missed a lot of school as a freshman, she chose not to tell her classmates about her disease. She said she felt lonely in high school because people didn’t really know her. She also didn’t make friends there because she missed so much school.

“I was my mom’s full-time job,” she said. “It took four years to get to a baseline where I was ok.”

When she got to college, Annie developed Interstitial cystitis and Desquamative Inflammatory Vaginitis and other side effects from being on Rituximab for five years.

“My freshman year at TCU I was very sick,” she said. “It came on as UTIs (urinary tract infections) and I kept being treated for UTI symptoms but nothing was working, obviously my medical history is more complicated than most and difficult for any college health center to understand. I wasn’t just a normal college student, getting UTI’s, it just didn’t make sense.”

By the time summer rolled around, she said she couldn’t hold her pelvic floor. She went to four different urologists who couldn’t help her. She was on strong bladder medications and on anxiety medication which helped her cope with her symptoms.

Her parents found a urologist who could treat her, but she said she was the youngest patient in the practice, which also included a lot of pregnant women. Those challenges were especially hard for the college freshman.

“No one is peeing out massive blood clots, even my friends couldn’t understand,” Annie said. “I was down at times, but my parents said you are going to get through this.”

Learning to Live With Vasculitis

It hasn’t been easy, Annie said, she has been through many ups and downs but she added, “in the past few years, I have gotten a better attitude.”

Annie is now off of Rituximab and is taking Azathioprine to treat her vasculitis. She has also started weekly subcutaneous IVIg treatments.

“I still struggle a lot and it still flares a lot,” she said. “It’s been easier to manage. I hope one day it will be a lot better. I don’t pee my pants in class so we’re doing better!”

Annie decided she was going to make friends in college. She didn’t want to repeat her high school years. She found people she could open up to.

“This is part of me and I want my friends to know all of me,” she said

She found classmates who could understand her need to stay in on a random Friday night, even though that is the last thing she ever wants to do. They make it better by staying in with her and supporting her. Her nursing friends even practice for their clinical days by plugging in her IVIG infusions.

She also found a professor who inspired her to use her experiences to write a book and to offer support to other children and teens who are struggling with vasculitis. She is excited to share her work and talk about coming out on the other side of her disease, no longer a monster or even a full-time job for her mother. She is searching for a publisher who can help her with her book and she hopes to start a blog to help children and teens struggling with a rare disease.

“My parents are so proud of me. I have done a huge 180,” she said. “I don’t know my next steps, but I want to reach kids with chronic illnesses.”