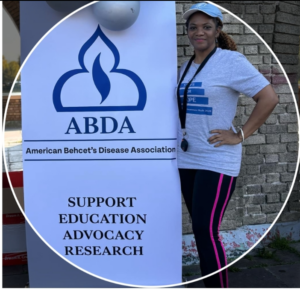

Kimberly Fisher Spreads Awareness About Behcets Disease as a Nurse and a Patient

Kimberly Fisher knows what it’s like to be told her disease is all in her head, to be thought of as someone who is just seeking pain medications and to be misdiagnosed for years.

She was diagnosed with Behcet’s disease, a rare form of vasculitis, in 2019, 10 years after experiencing her first symptoms. When she first heard the diagnosis, she didn’t know what it was, even though she had a career as a nurse. Now she is working to make sure nurses and doctors everywhere know about vasculitis and especially about Behcet’s.

Kimberly experienced her first symptoms in 2009 when she woke up with a severe headache. While readying her self to rise, she realized she was experiencing other symptoms, including a tingling on the side of her face and severe pressure in her head. As she tried to get out of the bed, her legs buckled and she fell to the floor. Her heart was racing and she couldn’t pull herself off of the floor. Her husband woke up and took her to the emergency room. She thought she was having a stroke.

Misdiagnosed

She was in the hospital for four days when a Neurologist told her she had not had a stroke, but he believed she had Multiple Sclerosis (MS). It took her months to get an appointment with a specialist and during that time, even though she was on medication, she experienced more symptoms. She had more tests before her visit because she was in and out of the hospital.

She was in the hospital for four days when a Neurologist told her she had not had a stroke, but he believed she had Multiple Sclerosis (MS). It took her months to get an appointment with a specialist and during that time, even though she was on medication, she experienced more symptoms. She had more tests before her visit because she was in and out of the hospital.

When she finally saw the Neurologist, he sent her for more tests and referred her to several other specialists, including cardiologists, orthopedic specialists, neuromuscular doctors, ophthalmologists, and speech therapists. After several more months, she learned that the tests and appointments showed she did not have MS, but no one was closer to figuring out her Behcet’s diagnosis. She was then sent to a migraine specialist.

Before she was diagnosed, Kimberly spent years in and out of emergency rooms where she was dubbed a frequent flyer. She accused of seeking pain killers, told to seek psychiatric help, and even dismissed within five minutes of arriving in an emergency room.

Not Believed

As a career nurse, she knew what they were doing was wrong. She also knew how to advocate for herself, but on her worst days, she didn’t have the strength or the emotional capacity to do so. She also realized that as a nurse, there had been times when she saw patients and didn’t believe them.

As a career nurse, she knew what they were doing was wrong. She also knew how to advocate for herself, but on her worst days, she didn’t have the strength or the emotional capacity to do so. She also realized that as a nurse, there had been times when she saw patients and didn’t believe them.

“I was guilty as a nurse of saying ‘there they go again,’” she said. “Of thinking this was a hypochondriac, or oh here they go again looking for drugs. Not until you are that person, that patient, is it real.”

Kimberly said she could hear the hospital staff talking about her and all she could do was wait and cry. “I was scared to ask them for help because they were talking about me, she said. “They would talk about me where other people could hear.”

As a nurse, she knew what they were doing was wrong, but she also felt helpless.

“These are the people I took oaths with to take care of patients and listen to them,” she said. “We need to go back and remember why we got into this. I left the hospital and when I got well enough, I made sure to write everyone about what happened.”

Cascading Symptoms

Before she was diagnosed, Kimberly had developed Pericarditis, an inflammation of the thin layer of tissue surrounding the heart, a pattern of uncontrolled hemiplegic migraine episodes, sharp chest pains, palpitations, constant muscles pains, fainting spells, shortness of breath, numbness and tingling in her upper and lower extremities, muscle weakness, difficulty talking, difficulty swallowing, nausea and vomiting. She experienced small myocardial infarctions – mini heart attacks, and mini strokes.

“Each specialist consulted with one another and agreed that something was definitely affecting almost every system in my body,” Kimberly said.

Finally a Diagnosis

She finally got a diagnosis when another nurse convinced her to travel from her Delaware home to the University of Pennsylvania. By then she was on disability and no longer working as a nurse, and had a host of different patent labels.

“It shouldn’t take that long and you shouldn’t have to go through mental trauma to get a diagnosis,” she said.

Raising Awareness

She works to raise awareness so no one has to feel like she did.

“Every Behcet’s patient isn’t like me. They aren’t in the medical field. They don’t have my connections,” she said. “I tell other medical professionals everybody should be treated with dignity and respect. Look at each person as an individual. We ask if there’s anything new at each appointment because we know something could be new.”

She hands out literature wherever she can and makes sure, if she finds some new literature, to deliver it to her rheumatologist.

She said colleagues are starting to open up to her message, instead of being offended by it. While she is no longer working as a full-time nurse, she is still involved in the nursing community. She is a member of the Delaware Nurses Association, Delaware Chapter of the Black Nurses Rock Foundation, the Foundation for Black Women’s Wellness and she runs her own business, KF Health Consults.

She said colleagues are starting to open up to her message, instead of being offended by it. While she is no longer working as a full-time nurse, she is still involved in the nursing community. She is a member of the Delaware Nurses Association, Delaware Chapter of the Black Nurses Rock Foundation, the Foundation for Black Women’s Wellness and she runs her own business, KF Health Consults.

She was thrilled to be a key note speaker at an American Heart Disease awareness walk. She brought along colleagues and friends so they could learn more about the disease. Whenever she has a platform – like her LPN nursing sorority where she’s considered a trailblazer – she uses it to educate and advocate for as many people as she can.

“If I can be on their side, as one of them, but also as a patient, it eventually will have a bigger impact,” she said. “It’s an honor to do this.”